I discovered Soma.fm two years ago on a Black Friday sale for iOS applications. The Soma.fm app was free for the day, so I downloaded it. Opening it on my iPad, I was met with what felt like a dated application: simply, there were rows of radio stations I could tap on and listen to. And tap and listen I did.

Internet radio fascinates me for several reasons. Largely, I’m drawn to compare this means of exposure to music against algorithmically driven, all-you-can-eat services like Spotify or Apple Music. These services have changed our relationship with music; bear with me while I enumerate a few, starting with the obvious:

- You can listen to as much music as you want for a fixed price (the price of one CD (from my youth, at least) gets you unlimited music for a month).

- The service "finds" and presents music to you, rather than you having to seek it out (of course, you can find music via search and browse-by-genre).

- Software has replaced the physical objects that represent the encapsulation of sound and music (no CDs, vinyl, tapes, etc.).

- The service collects data about you so that algorithms can be used to generate playlists and endless "radio" streams that are tuned to be enjoyed by you (among other purposes).

- The service can advertise to you (although, perhaps this is not dissimilar to seeing a poster for a new album at your local record store, for example).

Writing from the perspective of a listener, I’m omitting important differences for artists who sign up to use these services (for example: how much they get paid, tactics they might have to use to be discovered, how much they have to pay to be on the service, etc.). Notwithstanding, the differences from the days of collecting hardware music for listening are numerous.

My Music Streaming History

I’m going to get back to internet radio in a second, but before I do, let’s talk about my relationship to music listening subscription services in the last few years.

I signed up for a free Spotify account, probably around 2015. I recall being a little confused using it, and also that I was only able to listen to albums and playlists on shuffle — a limitation of not having a paid account. I didn’t use it much, but I do remember creating a "library" of artists. It certainly was novel to be able to simply add artists to my library; artists whose music I would have had to either buy, rip from the library or a friend, or steal if I wanted to listen to it on demand (sans internet connection, sans YouTube).

Fast-forward, and a friend suggested I try the now-shuttered Google Music. This time I got more into it, paying for the service and cultivating a large library. It was effective and I was happy with it. I mostly added artists I listened to already, and did little exploring.

A few years later, I switched to Spotify, for some reason or another. I cultivate a library. Sometime around 2019 or 2020, I start meeting people who have stronger opinions on the music industry, on supporting artists, and owning the music you listen to (in a DRM-free, offline way). Something changed in my mindset, and I decided that I’m not supporting the artists I’m listening to. I closed my account, and decided to spend a year using only Bandcamp to both find and buy new music. Each month, I bought a new album on Bandcamp, and tried to actively listen to it. I downloaded my Bandcamp collection. When I lost my phone and bought a new one, I made sure to get one that had a headphone jack and lots of storage. I transferred my library of audio files over to it — some 15 GB I’ve collected over the years.

This went on for a while, and was a pleasant experience. The importance of having my music offline was negligible; I’m so rarely offline. Paying artists through Bandcamp felt good, and I enjoyed using their "explore" section to find new music.

But then, my partner offered me to join their Spotify plan. Of course, it was cheaper than what I had been paying individually. And I was back in. The buffet is open. And here I am still today, wandering from table to table, feeling pleased with the sounds that the infinite algorithm of songs feeds me.

Take Soma, Feel Good?

As time goes on, I start to go back to Soma.fm. I toss it on at dinner, when I’m working, or when friends are over. Turning on Soma.fm means a few different things: I don’t have to choose what to listen to, I don’t always like what I hear, and when I do find a gem, it is an important discovery.

Eliminating choice

We are not strangers to having too much choice. Apple iTunes used to tout that they had millions of songs in their library. But you had to pay for them. Very different from today.

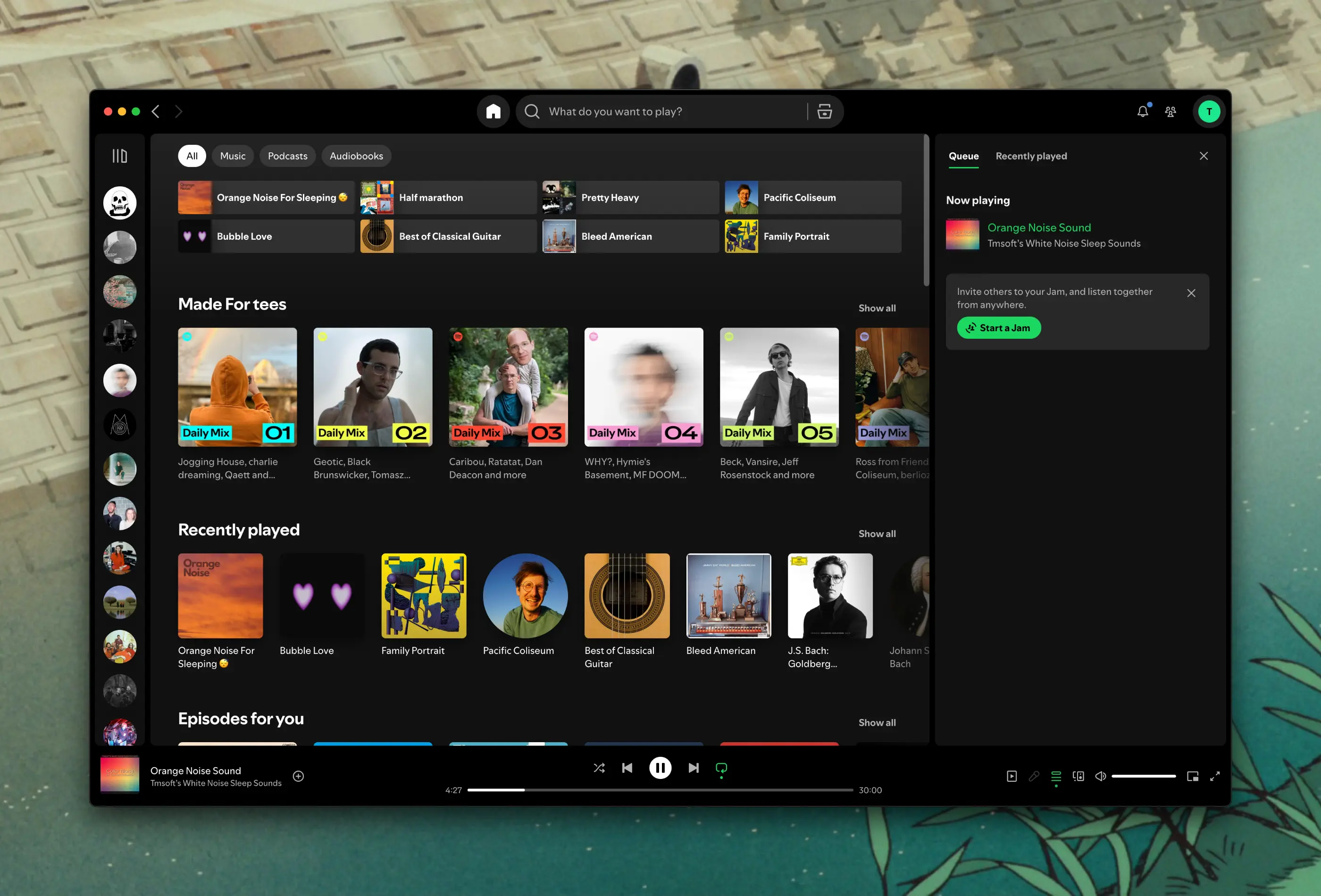

Today, you open Spotify and you open a door to an infinite room of music. As a listener, you get to decide what to listen to. Or rather, you have to decide what you want to listen to. The listener must reckon with the paradox of choice. It can feel like a chore. So, to mitigate that, you have this:

What is this? This is all the stuff I listen to either regularly or recently. My "Made for Tees" playlists are mixes of songs I’ve already heard with other, algorithmically suggested/similar songs that I will like. Rather than have to pick an artist, I can go to what’s comfortable. In fact, despite having access to a world of music, I end up listening to the same thing. Why haven’t I listened to David Bowie’s discography yet? Radiohead? Why haven’t I revisited Great Lake Swimmers, a band I enjoyed in high school? Why haven’t I explored music that came out of Africa in the 80s?

Many of these questions are perhaps a bit naive: Spotify needs to engage you and make it easy for you. Music listeners are trending toward listening to playlists (whether curated by human or software) rather than full albums. Hustling artists and musicians struggle to build a strong identity that raises them above the others they rub virtual shoulders with, in whatever playlist they’ve been slotted into.

Am I blaming Spotify for my inability to push myself to discover and listen to new music? Am I just a novice digital crate-digger? Maybe discovering new music doesn’t mean that much to me, anyway. All of these things could be true. I’ve never been particularly adept at finding new music, often gladly receiving recommendations from others. I don’t read music blogs to see what’s hip and cool. I won’t deny that I have been, and often am, in a listening rut — returning to my past comforts from halcyon times. But with all that said, I don’t think it’s all me.

What is different between this and listening to music on Soma.fm? How is listening to internet radio going to redeem my supposed struggle to find new music? Is it that I can connect with a real person who has cultivated the show? Perhaps, a little. Or maybe it’s that we can’t change the song; a small vexation that changes the relationship to the music.

I can’t switch tracks?

We need to be exposed to things that will not be predictably likeable. While my focusing in on the inability to change songs when listening to internet radio is credulous minutiae, I think it is indicative of a larger problem that we face. The true Soma is the infinite exposure to predetermined-likeable culture and consumption.

Obvious (and scary) examples of this are folks who find themselves being fed content from corners of YouTube that are violent, discriminatory, and inaccurate, all with addictive presentation that insidiously keeps you on the site. The creator of YouTube’s algorithm, Guillaume Chaslot, that makes this possible, now speaks out about the damaging effects of this.

Importantly, as Chaslot states at the beginning of the podcast episode linked above:

It was always giving you the same kind of content that you've already watched. It couldn't get away from that. So you couldn't discover new things, you couldn't expand your brain, you couldn't see other points of view. You were only going to go down a rabbit hole by design.

I don’t think music streaming services are nearing the dangers of toxic YouTube videos. But I am concerned about the likelihood of my exposure to new things, or inversely, the effects of always listening to what I already like. While I am maybe just a few clicks from exploring other genres, why would I, when the comforts of home are right there when I open Spotify?

When I tune into Soma.fm, I am frequently confronted by a mix of tracks I do and don’t like. In fact, the dissonance of this is so obvious as to be jarring; in contrast, listening to algo-playlists hardly ever knocks me out of whatever reverie I’m in.

And it’s uncomfortable. And that’s good, I think. It reminds me there is a world outside myself. It makes me think of things that I used to feel were uncomfortable, and now love. It makes me ask questions. It slows down time.

Funnily, Soma.fm. takes its name from the drug found in Brave New World, yet at least for now, it seems to, for my betterment, be having the opposite effect on me.

Occasionally, I do wonder if at some point I will abandon Spotify, again. I wish that I would either leverage it to actively explore a world of music at my fingertips, or I should just ditch it and keep listening to my songs, stored offline. The choice to be uncomfortable, however, is mine.

❦